Photo by Grayson Smith, USFWS.

Photo by Grayson Smith, USFWS.

Tularemia is a zoonotic disease that has recently re-emerged in parts of Illinois. Here’s an overview of this bacterial disease, along with tips on how to empower yourself to safely enjoy your outdoor adventures and protect your dogs and cats.

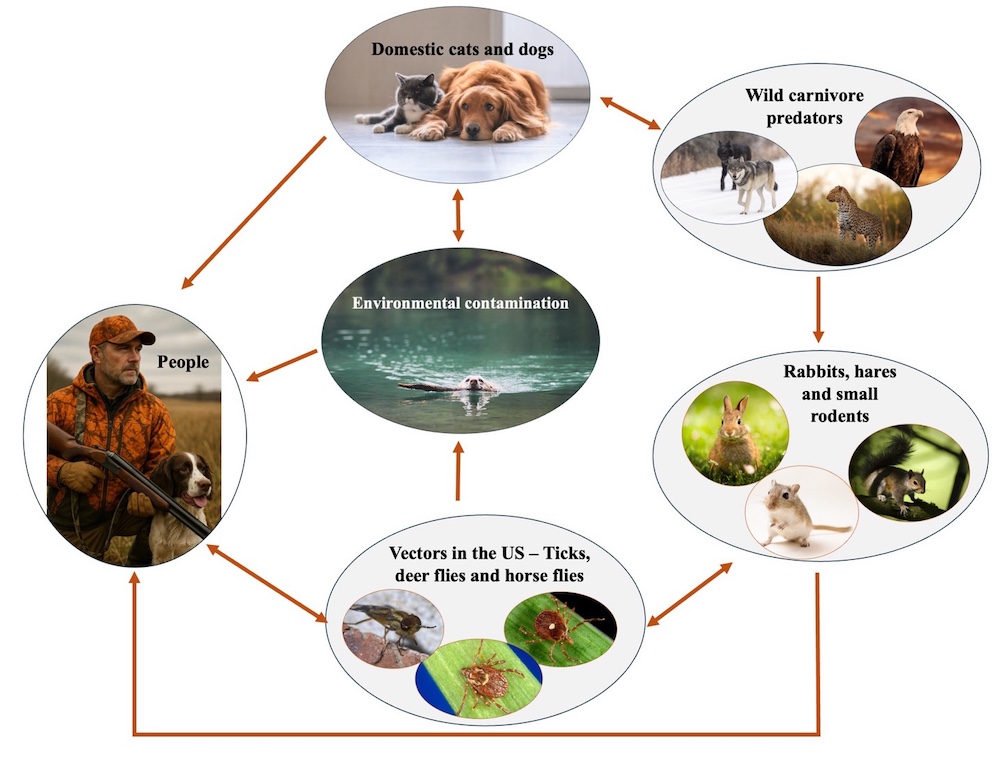

Tularemia is a bacterial septicemia (blood poisoning) that can affect people and more than 250 species of wild and domestic mammals, fish, reptiles and birds in North America and Eurasia.1 Rabbit fever or deer fly fever are other names for Tularemia, a classic zoonosis—a disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans. Humans can accidentally get infected via the skin while handling infected animals (e.g., dressing, preparing and improperly cooking wild game), ingestion of contaminated food or water, by inhaling dust or aerosols contaminated with Francisella tularensis bacteria, and from a vector bite such as ticks, mosquito and flies from the family Tabanidae.1,2 It has been suggested that birds can also act as vectors, as they may not be infected but carry the bacteria in their claws or beak. For example, a case report of a female jogger who was attacked by a common buzzard (Buteo buteo) that resulted in light scratches on the back of the head, and the development of Tularemia.3 Several other joggers were also attacked around the same time; however, only one additional case of Tularemia was reported. 3

The bacteria (F. tularensis) can survive for weeks or months in moist environments. Still, the bacterium is an intracellular parasite that can be easily treated with antibiotics following a prompt visit to a doctor and is effectively killed by heat and bleach.1,2

In August 2024, the Wildlife Medical Clinic at the University of Illinois reported noticing an increase in wild rabbits with Tularemia.4 Recently, in April 2025, case reports of Tularemia have emerged. Several cases of dead or ill squirrels were reported in Urbana, and a dead rabbit tested positive for Tularemia in central Illinois.5 While Tularemia can occur across the United States, it is not a common disease. When the incidence—the number of new cases of disease in a population over a specific period—increases, public health officials respond accordingly, providing recommendations for populations at risk.

Suggestions on how to reduce the risk of humans and pets becoming infected include:

1) Tularemia in Animals. Merck Veterinary Manual. Available online.

2) Tularemia. IDPH. available online.

3) Ehrensperger, F., Riederer, L. and Friedl, A., 2018. Tularemia in a jogger woman after the attack by a common buzzard (Buteo buteo): a” one health” case report. Schweizer Archiv fur Tierheilkunde, 160(3), pp.185-188.

4) Rabbit Fever on the Rise in Central Illinois

5) Deaths Reported in Several Area Squirrels, Tularemia Identified. Champaign-Urbana Public Health District. Available online.

6) Sharma, R., Patil, R.D., Singh, B., Chakraborty, S., Chandran, D., Dhama, K., Gopinath, D., Jairath, G., Rialch, A., Mal, G. and Singh, P., 2023. Tularemia–a re-emerging disease with growing concern. Veterinary Quarterly, 43(1), pp.1-16.

Dr. Nelda Rivera's research focuses on the ecology and evolution of new and re-emerging infectious diseases and the epidemiology of infectious diseases, disease surveillance, and reservoir hosts’ determination. She is a member of the Wildlife Veterinary Epidemiology Laboratory and the Novakofski & Mateus Chronic Wasting Disease Collaborative Labs. She earned her M.S. at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and D.V.M at the University of Panamá, Republic of Panamá.

Dr. Nohra Mateus-Pinilla is a veterinary Epidemiologist working in wildlife diseases, conservation, and zoonoses. She studies Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) transmission and control strategies to protect the free-ranging deer herd’s health. Dr. Mateus works at the Illinois Natural History Survey- University of Illinois. She earned her M.S. and Ph.D. from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Submit a question for the author

Question: Read your article on tularemia. You never mentioned what the symptoms are.